Hi there!

I hope you’ve been enjoying the warmer weather as much as I have. Yesterday, as I left my apartment, I saw what I thought was a snow flurry at first, but turned out to be the down feathers of a small bird being eaten by a red tailed hawk. The seasons are changing, and the wheel of life is turning! Finches are singing out the window in the morning! I can’t wait to go swimming and watch baseball.

We did our final Seals & Seabirds tour of the season last Sunday (March 2nd). It was a windy afternoon, and we had less than perfect views of the seals (many seemed to be in the water to get out of the wind) but I had a great time on my last winter trip down to the lower bay. If you missed this year’s tours, don’t worry: there are more coming next winter.

One of the things I like about my work, which involves keeping an eye on various natural areas and wildlife populations, is that I regularly encounter little mysteries about nature in NYC. On the seal tours, we had a few recurring ones. There was the small-scale fishing fleet we kept encountering in the bay—old lobster boats that looked like they were being put to work harvesting something else near the Statue of Liberty all winter (presumably not lobster). Then there were the red-throated loons that seemed to hug the New Jersey shoreline in that same area. Finally, there was the lone seal that, for a while, popped up right along Pier 26 in Hudson River Park on just about every tour.

The seal’s schedule seemed to overlap with the tour schedule, either because it was hauling out to sleep somewhere nearby, or because it liked to fish there at a certain tide, or because it found a convenient current to ride around the city—a kind of seal subway—that happened to synch up with our trips out to Swinburne Island (the tours were timed roughly with low tide). For all I know, it’s the same seal I saw cruising around the northern edge of Manhattan a few weeks back. The first time we saw it off of lower Manhattan, it broke the surface with a hefty oyster toadfish in its mouth, which it proceeded to devour alongside our boat to the delight and horror of everyone on board.

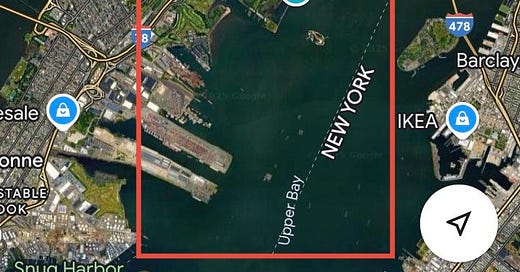

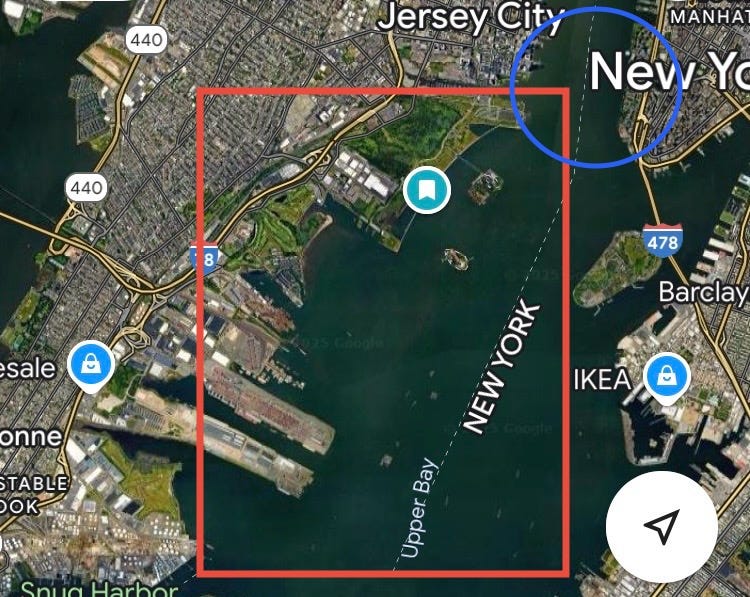

Anyway, I made a little map of the areas where these three mini mysteries overlap. The blue circle is roughly the area we saw our mystery seal, and the red rectangle is where the red-throated loons kept showing up, and where we’d run into the little fleet of old lobster boats fishing. I like to think they’re all related, and that the seal, the fishing fleet, and the loons are all over there for the same resource, but truth be told: I have no idea! I’d be happy to hear your thoughts on this, because speculating about things like that is fun.

NYBG Writing Class, and a Bird Tour:

I have a pair of upcoming events to plug, even though my spring/summer tour schedule is far from set in stone (if you work for a local environmental organization and want to schedule something, reach out! In addition to knowing a lot about nature, I am affable and easy to work with.)

The first is that in April and May I’m teaching a nature writing course at the wonderful New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. The dates and times for the classes are:

Wednesday, April 16th, 5:30pm-7:30pm (Virtual)

Wednesday, April 23rd, 5:30pm-7:30pm (Virtual)

Sunday, May 4th, 11:00am-2:00pm (NYBG).

It’s going to be a lot of fun. The idea is to think about the role of cities in nature writing and then help each other write. We’ll trace themes through different authors and periods, and unpack different ways of thinking about the environment. We’ll also discuss what distinguishes “nature writing” from other types of writing, and whether Henry David Thoreau was a cool guy, or a phony and a crank. It’s also a writing workshop! We’ll produce some writing, and then improve our own work together in a supportive setting. My career has been sort of unconventional and circuitous, but for whatever it’s worth, I’ll also share my personal experiences with the writing world and my own advice on how to pitch, and navigate professional relationships, promote your stuff, and all that.

If that sounds interesting to you, I’d love to see you there. You can sign up here.

I’m also leading a free bird walk at the wonderfully degraded (and wonderfully semi-restored) Sherman Creek, a stretch of Manhattan shoreline that seems almost tailor-made to highlight the things that this newsletter is about. That tour is on Sunday, April 27th at 8:00 AM. I never know exactly what’s going to come out of my mouth on these things, but I can definitely promise that I won’t stick to birds. The other day, I went over there at low tide and noticed that the wild oyster population seems be doing pretty well.

Beyond that, stay tuned! There will be a series of summer Bird Alliance walks along the protected shorebird area in Arverne/Edgemere this year, as well as some other fun opportunities to get outside and explore the natural world.

Some Memories of Eric Angel Ramos

I want to note the tragic passing of somebody who was a big part of the local marine biology community.

Eric Angel Ramos was a young scientist I met when I was at RISE in Rockaway. He worked as a research mentor in our Environmentor program, which basically meant that he took a handful of high school students under his wing for the summer to teach them about his work and helped them produce a science poster presentation for a colloquium at AMNH. It was a really cool program. The kids loved it, and the presentations always impressed people. If you were ever a mentor: thank you. I appreciate you!

Eric’s project at Rockefeller University was pretty flashy by our standards. He had a live octopus named Costello in a tank, which meant that the students who were working with him took the subway from Rockaway to Manhattan twice a week to study the animal up close. The idea was to observe changes in skin color and pattern that the octopus underwent in low-light and no light conditions, and then compare those changes to other environmentally triggered patterns and colors (predator evasion and hunting displays) to try and see if octopuses were “dreaming.” The research he produced ended up being kind of a big deal, and you can read about it here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/25/science/octopus-nightmare-dream.html

But I didn’t like Eric because he was successful. His attitude towards the kids and the program was exceptionally generous and patient. He was funny, and bright, and capable of adjusting on the fly to accommodate the whims of a program manager tasked with making sure 50 high school kids had something to do every minute of every day (me). He was a kind-hearted, easy-going guy, and he had a casual, friendly way of communicating. He was also cool! The students loved working with him.

Eric grew up in Brooklyn but had moved out of the city at various moments during his career. After the summer with the octopus he’d moved to Belize, and later to the west coast. In addition to all of his scientific work, he was guiding trips to Indonesia and Mexico as a naturalist with the Oceanic Society. He embodied the get-out-there-and-get-your-shoes-wet values that, if you’re reading this, you know I cherish. Once, during a phone conversation, I kind of casually asked him what he was feeding to the octopus, to which he replied “oh, I’m actually dealing with that now.” He had been grunting a little during our conversation, and it turned out that he was out at a marsh in Jamaica Bay with a shovel and a bucket, digging up fiddler crabs to feed to Costello while he talked on the phone.

Anyway, I learned just recently that he passed away in December and I wanted to say that even though he and I weren’t close friends or anything, Eric was a really good guy who seemed like he had a very bright future ahead of him, and I was very sad to hear about it.

Seal Facebook

One of Eric’s research areas before he studied octopus dreams was identifying individual marine mammals by anatomical features and other external markings. He worked on cetacean fins, and on manatees, building out databases that identified and tracked animals by the shapes of their fins, or their faces, or their scars. Some of that work is being adapted now to study harbor seals right here in New York City.

People are sometimes surprised when I tell them that nobody knows where the NYC seals go during the summer, but it’s true. They slip off into the water around this time of year and swim north to a breeding colony somewhere in Massachusetts, or Maine, or even Canada. We don’t really even know for sure how the seals that are here are using the city–how often they drift off to join other groups, etc.

There’s reluctance to attach a GPS collar to one of those animals, just because it would basically require tackling a 250 pound animal and freaking out the entire local population, so instead, scientists are trying to see if they can figure out how to identify individuals seals consistently. Seals might have distinctive looking faces, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to look at a specific animal and say whether or not it’s the same one that was around the day before, or the year before. Kevin Woo, one of the marine biologists who has been working with New York’s winter seals for decades, described individual harbor seal ID as “the holy grail of photo identification.”

It’s not that nobody can do it. Arthur Kopelman, a naturalist who leads winter walks out on the east end of Long Island has a system, but it’s not something he’s been able to teach other people.

“He’s been doing that walk for thirty years,” Kevin explained, “and he’s got a pretty good way of identifying seals, but only he can do it.”

It’s an interesting problem to try to solve, and it’s one that could potentially clarify all kinds of questions about how those animals live. Identifying individual seals from images could one day let scientists to go back and fill in gaps about the relationships between the seals that visit New York Harbor in the winter and the ones that form summer colonies along New England, as well as more NYC-specific questions about the relationships between the various groups of winter seals here in the city.

Woo and some of his colleagues have taken a version of the algorithm that the TSA uses at Airports and trained it on video footage of seals at the NYC aquarium, honing in on distinctive geometric points of their faces and their postures. It’s a neat first step in a process that might eventually tell us more about where some of the local NYC pinnipeds go during the summer. Maybe, at some point, it’ll solve the mystery of the seal that keeps popping up out of the water along Hudson River Park.

You can read more about Kevin’s work with his colleague Kristy Biolsi here.

What a beautiful report in every way!