Spirula!

I’ve mentioned before that my apartment is full of objects collected from beaches over the years–sea glass, shells, bone fragments, animal skulls, plastic army men, etc–and I promised at the start of this newsletter that I’d occasionally open up my home museum and share some of those things with you, so today’s Landlubber is going to be one of those. It’s about a small shell that my wife found a few years ago. Meet Spirula!

My wife and I both love beachcombing, which is nice, because it means I get some company during a normally pretty solitary activity (walking, head down, sometimes for hours). She found this little thing along a remote beach on the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica.

Because I’m the person in our marriage with all the field guides and books about nature, shell ID is usually my job, but this thing had me scratching my head. I don’t live in Costa Rica or travel out of the country very much, so you’d expect that some of the stuff on the beaches there would be new to me, but I do know enough about shells and their shapes to be able to spot an oddity.

This shell stood out for a few reasons.

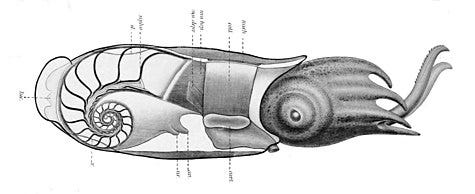

The first was that it didn’t corkscrew left or right but curved out in one direction in what’s known as a planispiral (like, “spiral on a plane”). Take a look at any spiral shell in your house—a conch, or a whelk, or a moon snail—and hold it with the aperture (the opening) at the bottom, facing you. The hole will almost certainly be on one side or another (in fact, it will almost certainly be on the right side, but that’s a longer story!)

But this shell had no slant. It wasn’t left-handed, or right handed. The smallest part was right in the middle. Flip it over, and it was a perfect mirror image of itself: a gentle curve that grew as it bent outward.

The best-known planispiral shell is probably the chambered nautilus, which is one of the handful of creatures still alive that still exhibit that type of growth. Like a nautilus shell, this little thing also appeared to have grown in neat segments, little air chambers whose internal pressure can be adjusted with an organ called a siphuncle.

The other odd thing that stood out was that it had what’s called an open coil—meaning that it didn’t cling to the previous growth as it wound out, but left a gap between sections–another fairly uncommon trait.

“It looks,” I mumbled, “kind of like an ammonite?”

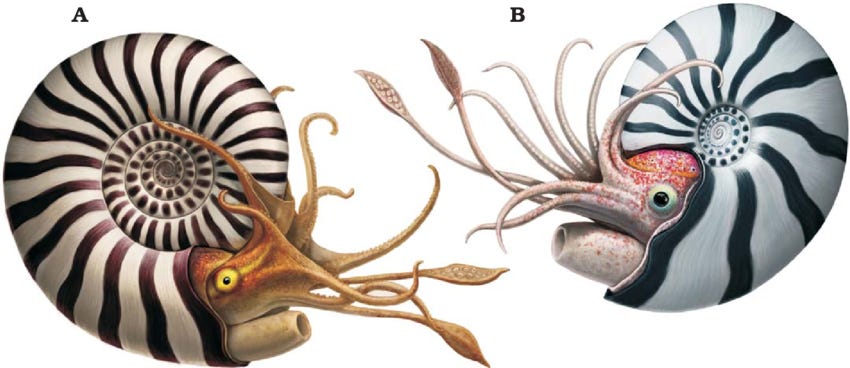

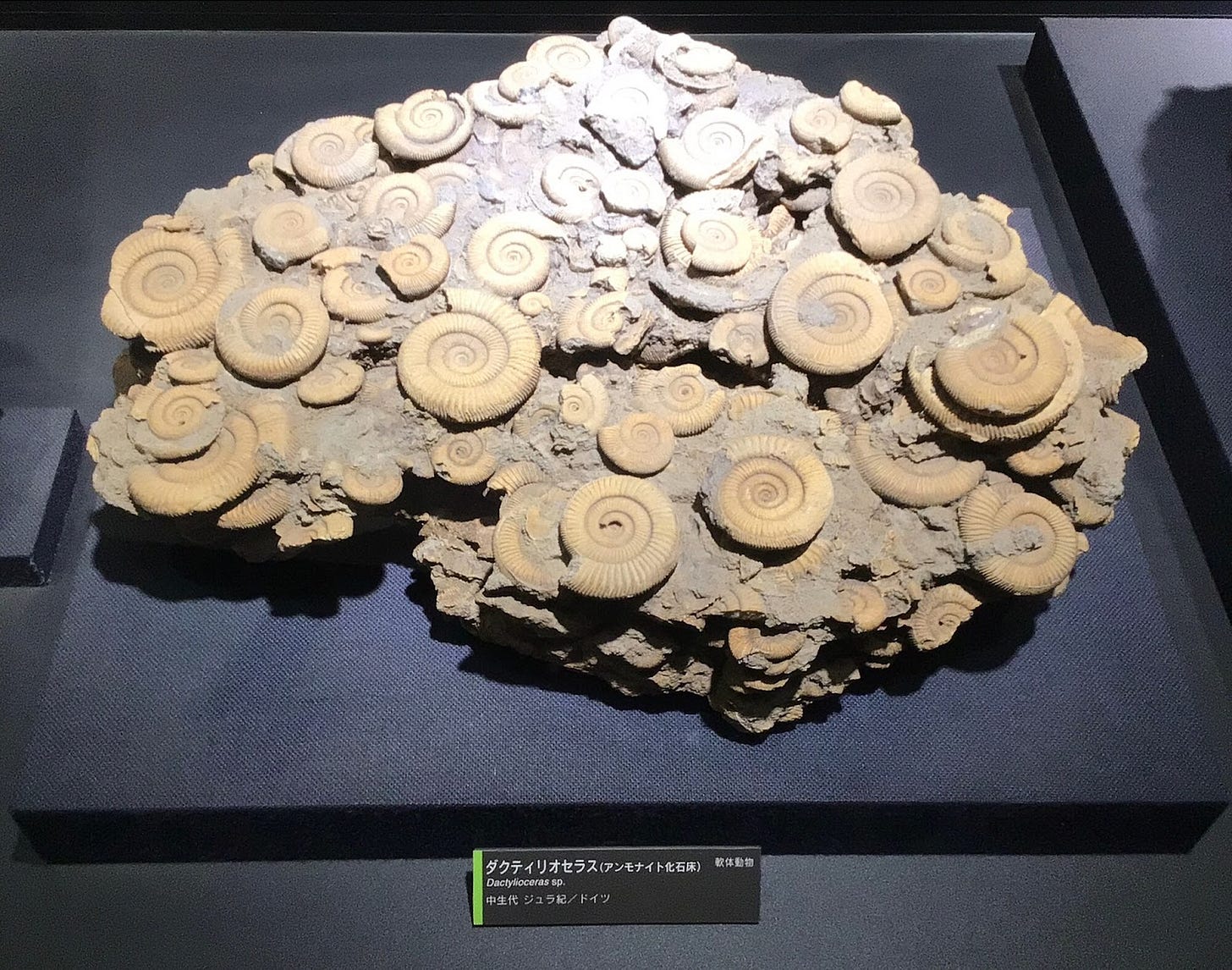

Ammonites (or ammonoids) are a group of shelled cephalopods that appeared in oceans about 450 million years ago and thrived for a little under 200 million years. They were free-swimming squid-like creatures that jetted around like nautiluses do today (at least, we think they did). Not all of their shells were planispiral, and not all of them were “open” spirals, but a lot of them were.

Time is kinder to calcium carbonate than flesh, and while lots of ammonite shells survived as fossils, very little soft tissue did, leaving some room for scientists (and goofs like me) to speculate about what they looked like and how they lived. They’re mysterious, eerie clues about an ocean that existed in the deep past.

Ammonites bowed out abruptly with the dinosaurs, exiting at the dramatic curtain call of the Cretaceous Period when an asteroid about the size of Manhattan collided with the earth (66 million years ago). All of which is to say: I was pretty sure it wasn’t an ammonite.

But ammonite wasn’t so far off, either.

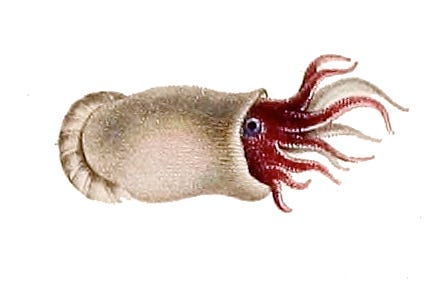

It turned out to be the internal shell of the Ram’s Horn Squid, Spirula, spirula, a small, deep-ocean cephalopod and a relative of those early, extinct cephalopods.

Ram’s horn squids aren’t quite as mysterious as ammonites, but they’re also not animals we know a whole lot about. They live in the gloomy mesopelagic zone, descending all the way down to 1000 meters below the surface, and have only been seen in the wild a handful of times. They were recorded on video for the first time as late as 2020 but their shells, which float and wash up on beaches around the world, are more common.

We know that they travel up and down in the water column, rising at night with the rest of the deep scattering layer (a massive daily vertical migration in oceans around the world), and that when they’re making those migrations, they usually have their tentacles pointed upwards. On video, they look a little bit like living elevators, ascending in more or less a straight line, which is probably due to their cool internal pressure regulator (aka the shell my wife found). We also know that they have a green light on their mantle (some people call them Tail Light Squid), which they presumably use to attract mates, lure prey, or both.

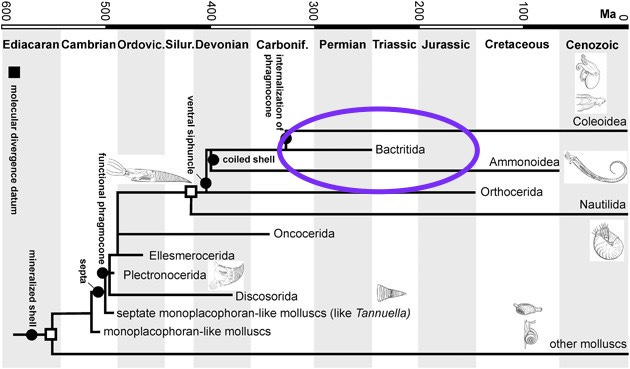

As far as their exact phylogeny goes, it’s kind of a murky picture. They’re the last cephalopods in an otherwise extinct order called spirulida, but scientists don’t agree on when it first emerged. They’re probably more closely related to squid and cuttlefish (and therefore ammonites) than nautiluses, but again, we’re talking about fossils from hundreds of millions of years ago. If it helps, you can take a look at this purple circle I added to an phylogenic tree from a scientific paper, which, to the best of my understanding, loosely the captures the area we think Spirula, spirula might fit in the big picture.

One of the things I like about shells is that in the messy, complex world of evolutionary biology where all kinds of forces are pushing and pulling in different directions, shells are relatively simple. You have to work hard to fully understand, say, the body (or even just the skeleton) of a fish—there’s a lot of noise in that signal—but with a shell, you have a relatively straightforward piece of equipment. It’s evolution sanded down to a digestible unit. It’s not that shells aren’t occasionally intricate or mysterious, but I find them relatively approachable, and because they tend to survive in sediment for a long time, we have a substantial record that allows us to trace changes back in time. To me, spirula is a geological refugee hiding out in the fleshy body of a deep sea creature—a little vestige of a primordial world that was obliterated by a space rock.

What a cool find, even if not rare. I know nothing about shells but it’s fun to learn that about the hole usually being on the right. Or was it left? See, already forgot 🙃