The Screwball Detective Writer Who Chronicled the Demise of Our Coastal Environments (and our Society)

Beach Reads, No. 1: Carl Hiaasen’s Florida

I’ve never really understood how people read at the beach. Beaches are distracting, overstimulating, full of light, water, noise. There’s wildlife to watch and seaglass to find. Books, which can’t get wet and require you to keep the sun out of your eyes and sit in a stable, comfortable position for an extended period of time in order to enjoy them, are, as far as I can figure, uniquely unsuited for that environment. Generally speaking, I do my reading at home, or the subway, although I’ve diligently lugged my books out to the water my whole life, only to leave them untouched when I’m there.

That said, the concept of the beach read—a book that because of its fast pace and straightforward language is easier to digest in a distracting environment—is one that makes lots of sense to me. I also love a good book about the beach, which is what Beach Reads is really about. This is the first in what will be a semi-regular Landlubber series that goes into books that are about the same stuff this newsletter is about. We’ll get to Melville and Carson and Sebald at some point, but we’re starting out with a love letter to the work of Carl Hiassen, both because he just released a new book, and because I happen to have read a bunch of his writing this winter. His novels are beach reads in both senses of the term, but I think they’re better and more interesting than a lot of the stuff that tends to get placed next to them on the shelf at bookstores.

The Wonderful, Ugly World of Carl Hiaasen

Carl Hiaasen is a former Miami Herald writer-turned novelist who writes satirical mysteries about the weird, wonderful, and occasionally… less than wonderful state of Florida.

After getting his start at the Herald’s city desk, where he churned out gems about racetrack tycoons and other so-called “greedheads” that he saw plundering Florida’s natural resources and public funds for profit, he began a career as a fiction writer, transplanting the outlandish characters and settings he encountered in his reporting into novels. Since 1986, when he published Tourist Season, Hiaasen has written around 20 books for adults, as well as a handful of novels for younger readers (all while working as a Herald columnist). He’s also published three collections of his newspaper writing from over the years: Paradise Screwed, Dance of the Reptiles, and Kick Ass.

The majority of his books are detective novels set around Miami and the Florida keys: elaborate mysteries that take readers on far-fetched adventures through the tabloid underbelly of the sunshine state. The main characters are mostly classic noir dudes— tragic, impulsive private detectives who drink a little too much, and care way too much—but the world they move through is a magically rendered, hilarious hodgepodge of Florida sleaze. Hiaasen’s books feature billboard lawyers, real estate crooks, plastic surgeons, mob bigwigs, hotel tycoons, strip club owners, and just about every type of con artist you can imagine. His upcoming novel Fever Beach dives into the white supremacist idiot-politics of the Proud Boys, a spiritual and literal successor to his 2020 book Squeeze Me, which dealt with palace intrigue among the Mar-a-Lago set.

As several recent reviewers have pointed out, Trump-era politics already seem like something out of a Carl Hiaasen book. The president and his band of vain, right wing dipshits are basically just versions of the trashy, scammer types that Hiaasen has been feeding to alligators for decades. If Don DeLillo is the prophet of our uncertain post-9/11 age, Hiaasen feels like the equivalent for the me-first ethos that, in the last decade or so, seems to have ballooned out to absurd proportions. As Slate’s Dan Kois put it: “nearly 40 years and 20-plus books later, what was happening to Florida is now happening to the entire country.”

But as I wrote at the outset of Landlubber, I’m not here to write about politics unless they have to do with the ocean! What I love about these books is their nature ethic: deeply felt sentiments about the environment that are pretty compatible with the editorial line over here at Landlubber. At the end of a Hiaasen novel, when the last severed arms have been tracked down and explained, and the last crook eaten by an alligator (or a shark, or a woodchipper) the real main character—the one Hiaasen returns to repeatedly, and would never write about with disdain—is Florida’s wounded, spectacular natural landscapes.

Again and again, Hiaasen’s goofy, elaborate plots return to the Everglades, the estuaries, and the remote key islands to make the point that the the manatees, mangroves, osprey, etc. are the big picture losers in the rube gold machine of insurance scams and real estate ventures that passes for society in his Florida.

One of the premises of this newsletter is that the fatal flaw in our relationship with the coastal environments around us (or a large part of it, anyway) is that we’ve forgotten how to see them, which makes us incapable of interacting with them in a healthy or clear-headed way. We don’t notice the sewage spilling out into the harbor, or see the wetland that was paved over or dredged up to create a parking lot. We’ve closed ourselves off from the water’s edge in every conceivable way (perhaps, even, by putting our noses into a book at the beach), and as a result, we’re all a bunch of kids trampling the dune vegetation.

Florida’s environmental history is an epic showdown between outlandish greed and spectacular coastal beauty: a story of developers and crooks and colonists who, over the years, have done battle with some of America’s most stunning, precious landscapes. It’s a place where enormous, prehistoric reptiles hide in drainage ditches below meticulously pruned lawns and golf courses, occasionally eating people’s pets, and where invasive species from all over the world—from burmese pythons, to iguanas, to giant snails—do battle with the native fauna. It’s got Disneyland, and Jimmy Buffett’s odd American fantasies, and Tiki bars. Whatever happened to our relationship to our coastlands and wetlands, the Sunshine State seems to be involved. Skip Wiley, the charismatic villain of Tourist Season puts it as follows:

The only thing that ever stood between the developers and autocracy was the cursed wilderness. Where there was water, we drained it. Where there were trees, we sawed them down. The scrub we simply burned.

The bulldozer was God's machine, so we fed it. Malignantly, progress gnawed its way inland from both coasts, stampeding nature.

Today the Florida most of you know-and created, in fact-is a suburban tundra purged of all primeval wonder save for the sacred solar orb. For all you care, this could be Scottsdale, Arizona, with beaches.

Let me fill you in on what's been going on the last few years: the Glades have begun to dry up and die; the fresh water supply is being poisoned with unpotable toxic scum; up near Orlando they actually tried to straighten a bloody river; in Miami the beachfront hotels are pumping raw sewage into the Gulf Stream; statewide there is a murder every seven hours; the panther is nearly extinct; grotesque three-headed nuclear trout are being caught in Biscayne Bay; and Dade County's gone totally Republican.

A lot of Hiaasen’s stuff feels like an effort to splash the estuary’s (befouled) water on our faces, not only to challenge our delusional notions of the coast as a giant playground, but to help us see the sewage and toxic sludge and agricultural runoff being poured in there. More often than not, his farcical crime plots end up giving way to a broader conspiracy that examines our mistreatment of nature, and our place in it. They’re also a lot of fun.

I’d say that if you’re looking for something to read at the beach this summer, you could do a lot worse than one of his books. I’ve included my favorites below in no particular order, although I haven’t read everything by him. You can find a full list of his books on his website, including the just-released Fever Beach.

Tourist Season (1986)

Tourist Season follows semi-disgraced Herald writer-turned private eye Brian Keyes as he trails a screwball terrorist group that aims to depopulate Florida by murdering tourists, members of the chamber of commerce, snowbirds, and various other parties perceived as guilty in the state’s defilement. Basically, they want to scare everyone off and turn the land back into the primeval wilderness that existed before it was developed.

“We’re gonna empty out this entire bloody state,” raves the group’s impulsive, charismatic leader Skip Wiley. “Give it back to Tom and his folks [the Seminole]. Give it back to the bloody raccoons. Imagine all the condos, the cheesy hotels, the trailer parks, the motor courts, the town houses, fucking Disney World–a ghost town, old pal. All the morons who thundered into Florida the last thirty years and made such a mess are gonna thunder right out again…the ones who don’t die in the stampede.”

This is the novel that most openly lays out the ecological ideas at the heart of Carl Hiaasen’s work: a way of looking at the environment that’s (a little) more nuanced than “nature good, people bad.” Skip Wiley, nominally the book’s villain, is irresistible, tragic, doomed. Hiaasen doesn’t endorse Wiley’s ideas, but he comes pretty close, flirting with them, and batting them around to showcase their appeal. While they might not justify murder, they make you feel that it’s fair game for the author to plop a few fictional characters into an old-world ethical universe that punishes them severely for participating in this dishonest relationship to the environment.

Skin Tight (1989)

A madhouse plastic surgery caper, Skin Tight skewers the grotesque vanity of its moment and mourns a rapidly vanishing old Miami. The story follows disgraced hermit Mick Stranahan who, after departing from the US Attorney’s office and settling in for a peaceful life on an inaccessible stilt house on Biscayne Bay, finds himself sucked back into a cold case when a would-be assassin shows up at his front door on a skiff. The plot features a whole array of hapless villains who should have taken powerboat handling classes, and it’s a lot of fun to watch them struggle out to Stranahan’s dock. It’s also got a homicide-by-mounted-marlin-bill, a sinister landscaping company that uses its wood-chipper for evil, a goon with a prosthetic weed-whacker for a hand, and a few plastic surgeries that render crucial characters unrecognizable at key moments.

Skin Tight is also an elegy for the seedy-but-simple way of life in Stiltsville, a bygone neighborhood out on Biscayne Bay’s tidal flats, where Miami’s outcasts and crime figures once deigned to live in closer communion with the water around them. Amid all the goofy wackiness, there are delightful scenes scattered throughout where Stranahan, an absurd misanthrope, is enjoying the quiet water and the sea breeze in his derelict stilt house.

Double Whammy (1987)

If you’d asked me before I picked up Double Whammy if I was interested in reading 387 pages about tournament fishing for largemouth bass, I would have said “no,” but I’d have been wrong. This book rules. Double Whammy follows private eye R.J. Decker who, after being hired to investigate cheating at big money bass fishing competitions, finds himself caught up in a web of murder and intrigue.

Here’s Hiaasen on largemouth bass:

According to the sporting goods industry, more millions of dollars are spent to catch largemouth bass than are spent on any other outdoor activity in the United States. Bass magazines promote the species as the workingman's fish, available to anyone within strolling distance of a lake, river, culvert, reservoir, rock pit, or drainage ditch. The bass is not picky; it is hardy, prolific, and on a given day will eat just about any God-awful lure dragged in front of its maw. As a fighter it is bullish, but tires easily; as a jumper its skills are admirable, though no match for a graceful rainbow trout or tarpon; as table fare it is blandly acceptable, even tasty when properly seasoned. Its astonishing popularity comes from a modest combination of these traits, plus the simple fact that there are so many largemouth bass swimming around that just about any damn fool can catch one.

Its democratic nature makes the bass an ideal tournament fish, and a marketing dream-come-true for the tackle industry. Because a largemouth in Seattle is no different from its Everglades cousin, expensive bass-fishing products need no regionalization, no tailored advertising. This is why hard-core bass fishermen everywhere are outfitted exactly the same, from their trucks to their togs to their tackle. On any body of water, in any county rural or urban, the uniform and arsenal of the bassing fraternity are unmistakable. The universal mission is to catch one of those freakishly big bass known as lunkers or hawgs. In many parts of the country, any fish over five pounds is considered a trophy, and it is not uncommon for the ardent basser to have three or four such specimens mounted on the walls of his home: one for the living room, one for the den, and so on. The geographic range of truly gargantuan fish, ten to fifteen pounds, is limited to the humid Deep South, particularly Georgia and Florida. In these areas the quest for the world's biggest bass is rabid and ruthless; for tournament fishermen this is the big leagues, where top prize money for a two-day event might equal seventy-five thousand dollars.

Double Whammy moves north from the busy glass skyscrapers of Miami to the rural, racist backwaters in their orbit. Hiaasen skewers the self-styled hillbillies in quarter-million dollar skiffs while giving some space to the genuine magic these men chase on those misty freshwater ponds at sunrise. Ultimately, the backwater fishing plot snowballs into larger intrigue about artificial lakes, suburban development, and Evangelical television networks: a follow-the-money water degradation scheme in the tradition of Chinatown. It’s also notable for introducing Skink, the road-kill-eating, backwoods-living AWOL former governor, and one of Hiaasen’s more outlandish and memorable antiheroes. A kind of spiritual successor to Tourist Season’s Skip Wiley, Skink is an environmentalist nut and an Enkidu-type wildman who, seeing corruption and ecocide around him, doles out old-world punishment left and right (in one scene by spit roasting and eating the toy poodle of another character whom he perceives to have sinned against Florida’s natural environment.)

Skinny Dip (2004)

The first Carl Hiaasen novel I ever read, Skinny Dip features a marine biologist on the payroll of big-ag who tries to murder his wife Joey by shoving her off a cruise ship on their anniversary. She survives by clinging to an enormous bale of marijuana, losing her clothing in the process. When she washes up, she’s discovered by none other than Skin Tight’s misanthropic hero Mick Stranahan. Stranahan, (still disgraced and reclusive, but having traded his stilt house for a place on a small remote key island) helps her track down her evil husband, exposing a plot to poison the Everglades with runoff along the way.

Razor Girl (2016)

The title refers to a character named Merry Mansfield, a con artist who gets into deliberate fender benders. Her signature scam involves rear-ending her victims and then staging herself to look as if she caused the accident by shaving her private parts behind the wheel, before asking her lust-struck marks for a lift (this wild plot line is inspired by events that Hiaasen read about in the Florida papers, although it feels almost too perfect to be true). The hero is Andrew Yancy, a police detective in the Keys who has been downgraded to restaurant health inspector, and is featured as the main character in a few other Hiaasen books (including the recently adapted-for-television Bad Monkey). Other irresistible details include a plague of giant Gambian pouched rats that terrorize local restaurants, and crooked businessman Martin Trebeaux, owner of a sand replenishment company called Sedimental Journeys who’s on the run after supplying a mob-run resort with “a slapdash mixture of crushed limestone, recycled asphalt fragments and broken glass” instead of the real stuff, leaving the feet of tourists covered in lacerations.

Native Tongue (1991) and Stormy Weather (1995)

The other two novels that feature the aforementioned Skink, these are wacky environmental tragicomedies involving, respectively, an exotic animal park beset by environmental terrorists and the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew. In both books, a bunch of animals get loose, and clueless tourists are punished for their callous disregard for the cosmic rules of Hiaasen’s Florida.

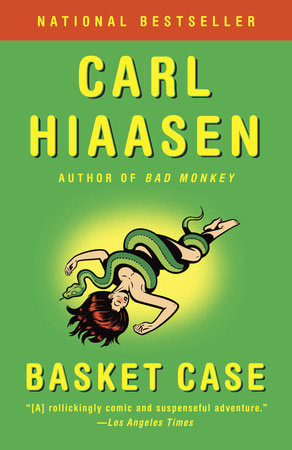

Basket Case (2002)

I haven’t read this one, but Hiaasen wrote it with his long-time friend and fellow coastal misanthrope Warren Zevon. I’m a big fan of both of them, so this is next for me.