Fish Migration Celebration

A Floating Parade for the Hudson's Spectacular, Invisible Migrations

Hi there subscribers! This newsletter turned one last week. Happy birthday Landlubber! The anniversary coincides more or less with the date of the General Slocum disaster (June 15th!) You can read the first ever Landlubber, about that accident, here. I’ve had a lot of fun writing these this past year, but my favorite thing about doing this has been getting to know all of you. I’ve loved corresponding with everyone who ever responded to one of these, and meeting the many readers who have come on my tours in real life. I’m looking forward to another year along the water with all of you! As always, a special thanks to those of you who choose to pay for a subscription. I’m very honored that you find this project worth the five bucks a month, and if at any time you feel like you need that money for something else, I’ll understand. To all of you who choose to stick with the free subscription, I love you all the same, and thanks for reading! If you feel like showing your appreciation for the work I do on these, just forward this along to anyone you think will enjoy it. Money is great, but at the end of the day I’m in this racket for attention.

I enjoyed this essay from Robert Francis’s excellent Bird History last month! Robert is an great writer and historian, and I had the pleasure of having him workshop the piece in my Nature Writing in Cities course at the New York Botanical Garden earlier in the Spring. I’m always amazed at his ability to find incredible, outlandish quotes from 19th Century bird discourse.

Ryan Mandelbaum’s always great newsletter eyy i’m walkin here had a lovely recent feature on the discovery of a cryptic population of dusky salamanders in one of NYC’s most neglected public parks. I also continue to recommend buying Ryan’s NYC field guide Wild NYC, which is a book I wish I’d had in my home growing up.

I’m leading Classic Harbor Line boat tours of the East River’s abandoned islands and their wonderful wading bird colonies on Sunday July 27th At 7:30 PM, Sunday, Aug 24, 6:35pm, and Monday, Aug 25, 5:30pm. If you don’t want to wait for one of my dates, the boats go out every Sunday and Monday, and Gabriel Willow is doing the other dates. The link to book those is here!

I’m also doing a series of free bird walks out along the city’s ocean-facing beaches in Arverne and Edgemere, on the boardwalk along the protected shorebird area in Rockaway. Dates for those are: Saturday 7/12, 9:30-11:00 AM, Sunday 7/20, 9:30-11:00 AM, Wednesday 8/13, 6:00-7:30 PM, Saturday 8/23, 9:30-11:00 AM, and Saturday, 9/6, 9:30-11:00 AM (Registration not required, but helpful, especially if you want me to try to bring binoculars for you!)

I’ve been rereading Moby Dick for like the fourth time. I get no points for originality with this opinion, but: I think it’s the best novel ever written. I’m considering doing a Moby Dick book club as a special perk for paying subscribers—something that could happen in the chat feature on Substack, with some zoom calls and subscribers-only newsletters interspersed. Let me know if that’s something that interests you!

While Landlubber was turning one, ‘JAWS’ celebrated its 50th birthday. Friday marked a half-century since the theatrical release, an anniversary that gives me as good an excuse as any to write about one of my favorite films. Stay tuned for that! In the meantime, I hope you enjoy this dispatch from New York’s first ever Migratory Fish Celebration.

Summer is the busy season for newsletters about coastlines. In the Northeast, this is the time of year we associate with swimming, and boats, and shorelines. We take the majority of our beach adventures these warm months, cramming every ritual involving the ocean or the water between Memorial Day and Labor Day. At Landlubber, we’re all about changing that, and opening up the colder seasons for coastal romps, sojourns, and *ahem* seal and seabird tours, but we also believe that June has room for one more annual holiday that brings us out on the water. Last Saturday (June 14th), I was delighted to ring in the first ever Fish Migration Celebration with the good folks at Riverkeeper.

The Fish Migration Celebration is our newest (and my new favorite) local holiday. It honors the enormous wave of sea life that moves from the Atlantic up through the Hudson River every year: an incredible, largely invisible mass-migration every bit as spectacular as the waves of birds and insects we see up on our side of the water. That phenomenon is, in the words of President and official Riverkeeper Tracy Brown, a “Serengeti-level event;” a mass migration of fish from all over the place that surges past Manhattan unseen. The Fish Migration Celebration is about honoring those creatures, many of which travel thousands of miles to get here.

The honorees were animals that are dear to my heart: American shad, Atlantic striped bass, the assorted local river herring species, the American eel, and the mighty, prehistoric Atlantic sturgeon (all of which, I believe, have been given some space in this newsletter in the past). Four out of five are anadromous fishes, meaning they migrate from the ocean into the Hudson to spawn. The American eel, born in a still undiscovered area near the Sargasso Sea, is the only reverse commuter, a catadromous fish that, after being born in the ocean, migrates inland and up the Hudson to grow up. Its complex life-cycle involves multiple dramatic physiological transformations and ultimately, a return trip out to sea to spawn and, we assume, die.

I’ve been lucky enough to meet some of these fish up close through my work and my fishing adventures. Shad were basically extinct in the Hudson by the time I picked up a fishing rod, but I’ve held little glass eels in my palm on surveys, and watched striped bass surge back into the surf after releasing them. I’ve even been lucky enough to see Atlantic sturgeon breach in the city a few times, breaking the surface before crashing back down (a mysterious behavior scientists are still working to explain). But most New Yorkers never get to see those fish. They sneak by in the Hudson, hidden in the cloud of microorganisms and silt that gives our river its murky brown-green hue.

Part-concert, part flotilla, part puppet parade, the event was a raucous set of overlapping, interconnected celebrations on land and sea. It was a big, collaborative effort, the kind of tireless all-hands-on-deck initiative that reminded me, with fondness and a little bit of dread, of my days working full-time at non-profits. Brown graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design and worked in the arts before moving into environmental conservation, and in addition to maritime and environmental groups, the organization had enlisted the help of Heather Henson’s puppetry collective Green Feather, composer Treya Lam, puppeteer Greg Corbino, futurist marching band Funkrust Brass Band, and other local artists, as well as local high school students. It was a homecoming party for returning striped bass who come back every year to spawn before making summer journeys coastwise, and a baby shower for the little glass eels drifting in from the ocean to spend up to a decade here. For American shad, which are nearly extinct in the Hudson, the celebration was, I suppose, something of a New Orleans funeral.

The fish themselves went unseen—a familiar problem that has followed me throughout my career working in marine environments. Birds are right under our noses, waiting to be discovered by anyone who glances their way, but it’s not as easy to build those intimate connections with marine life. Those animals are below the water, blocked off by bulkheads and riprap. The distance gives fish an elusive, mysterious quality that I find enchanting, but it also makes it difficult to get to know them and to be considerate of their needs. It’s an eternal dilemma of the ocean-obsessed, the Little Mermaid issue of them being down there, and us up here. A century ago, we knew the local fish from our dinner tables, but today, they’re basically strangers to us.

“It’s happening right now, right out here,” Brown announced. “All of these fish that we’re talking about are making their way up the river.”

New Yorkers are constantly rediscovering the water around them, and there’s a new generation poised to inherit an estuary that’s in better shape than it was half a century ago. Many young people were in attendance, some sitting on the grass with their own homemade fish puppets. The program began with songs written by students at the NYC Harbor School, a public high school on Governors Island founded in 2003 that, on top of teaching normal subjects like math and English, trains students in marine trades such as aquaculture, vessel operations, and ocean engineering. Composer Treya Lam, who had worked with the kids on the songwriting process, performed most of them with an acoustic guitar.

The lyrics had charming, unmistakably teenage touches. River herring were honored with a moody Gen-Z dirge about a fish who doesn’t want to spawn, a song dripping in environmental angst (“if we are what we eat/ am I the plastic left in the street?”). While Lam sang and played guitar, fish puppets made by students out of foil balloons and Gatorade bottles they’d salvaged from city beaches bobbed on the lawn. The final song, written and performed by graduating senior Dee Littlepage was a folksy round that had the audience singing in overlapping sections about the various life stages of the American eel. Then, just as the parade was getting underway, the first drops of rain started to fall.

“Here comes the earth,” Brown announced, “reminding us who’s boss, as she always likes to do!”

FunkRust Brass Band hopped to life, with tubas, drums, face-paint, sequins, and metallic spandex swaying back and forth. The bandleader belted the chorus of an original composition, a call and response (“Have you heard? The fish are coming!”) DayGLO lantern puppets from Green Feather depicted the migratory fish of the day, as well as seahorses, pipefish, crayfish, and other creatures that live in local bays and streams. Several younger children in the audience with homemade fish puppets, joined the eclectic school as it made its way inland, with paper plate constructions right alongside elaborate, professional puppets rigged to swim through the air in the breeze. At the Westside Highway (a road that was itself saved by Riverkeeper in the 1980’s during a contentious dispute over a plan to replace it with a tunnel in the river) the parade turned around and made its way back towards the water to greet the boats.

The rain came down in earnest just as the flotilla appeared, soaking puppets, puppeteers, and sailors.

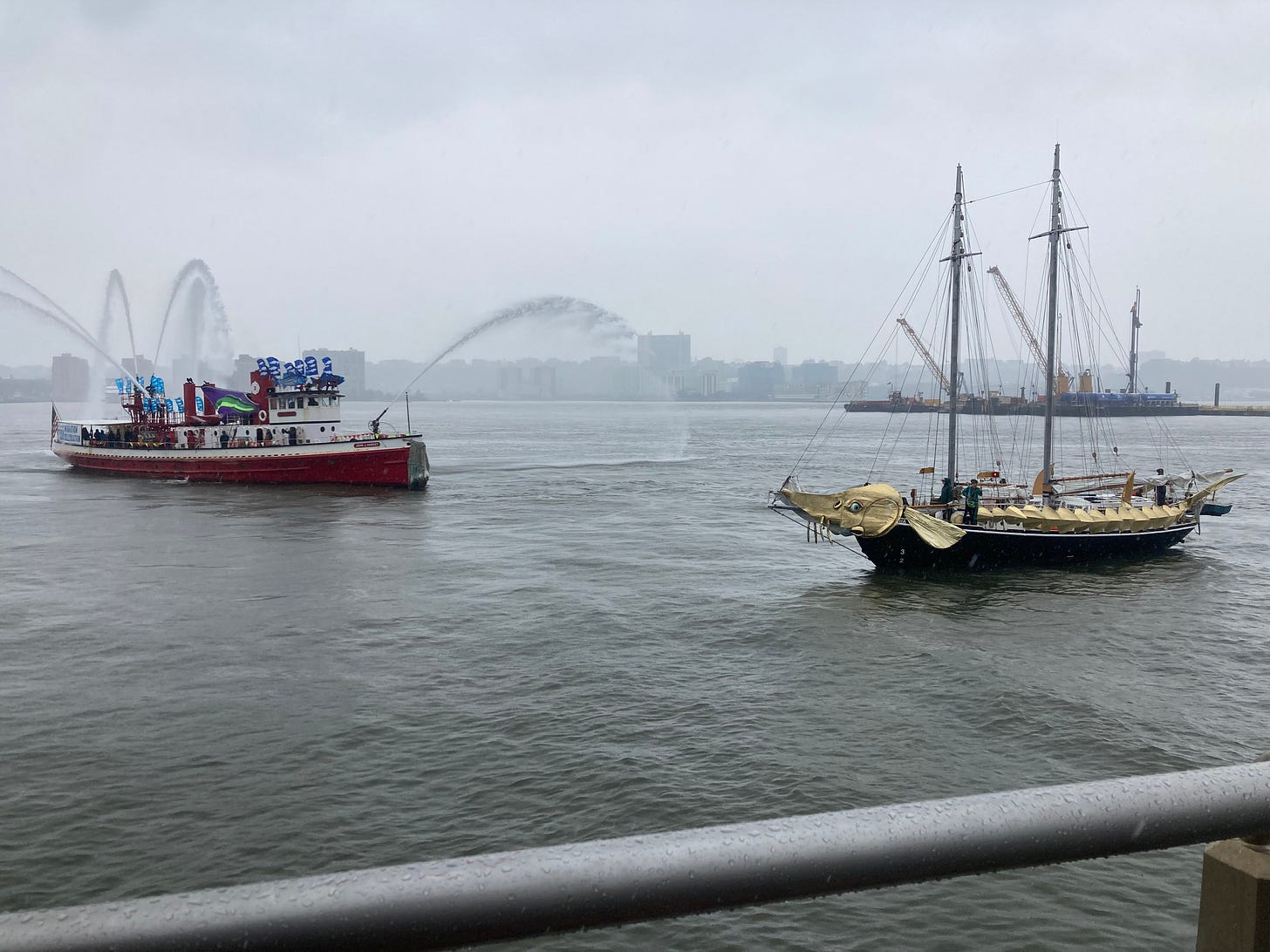

The boats had also dressed up for the occasion. Riverkeeper patrol boat The Fletcher was draped in flags bearing American shad, while the organization’s smaller science vessel the Bob Boyle tagged along with big blue cutouts of river herring fixed to each side. Retired fireboat John J. Harvey, rigged up with huge banners bearing striped bass and American eels, shot streams of water back at the sky with its cannons. Everyone huddled under the folding tents along the edge of the pier (I took cover with Hudson River Park Trust, whose table featured a large plastic model of an oyster toadfish).

The star of the fleet was the Appolonia, a 64 foot schooner built in 1946 and retrofitted in 2020 for small-scale, sail powered cargo shipments along the East Coast. The ship had undergone another makeover for the occasion, transformed by puppeteer Greg Corbino into an enormous, golden Atlantic sturgeon, scutes and all. As the crew dropped sails along the pier, Corbino worked the bow, pulling lines to roll its enormous green eyes back and forth and flap the surfboard sized pectoral fins. After some fanfare alongside Hudson River Park, the fleet moved north towards Inwood to stop at Dyckman Marina, following the paths of the migratory fish on its way up to the Hudson River Music Festival in Croton.

The flotilla had set sail early in the morning from Brooklyn Bridge Park to intercept the various land ceremonies, a kind of synchronized, herculean feat that involved moving equipment, puppets, people, and boats up and down the River by land and sea. One Riverkeeper staffer told me privately how many hours of sleep he had gotten in the last week, and it was a small number. Non-profit work is hard, but that effort felt like a fitting tribute to the fish at the heart of the celebration. Many of those animals swim thousands of miles each year, moving between nations and climates to make their spawning appointments. They travel, in their ocean journeys, as far north as Iceland, and as far south as the Caribbean before returning to the Hudson each Spring.

Tracy Brown, having taken over as President and Riverkeeper in 2021, has inherited a slate of decades-old environmental battles, some resolved and others ongoing. The Newtown Creek and Gowanus cleanups are inching along. As of last fall, the organization is suing the states of Delaware, New York, and New Jersey on behalf of Atlantic sturgeon for failing to enforce the Endangered Species Act . Water quality concerns and habitat issues continue to be areas of focus, with an ongoing initiative to remove industrial-era dams that block alewives and blueback herring from entering the streams they need to pass up to spawn. But the other part of the work involves more slippery, human stuff: bridging the distance we’ve imposed between ourselves and the marine ecosystems around us.

Despite the historical overfishing, and the wholesale befoulment of the estuary in the 19th and 20th centuries, it feels like kind of a hopeful moment for New York Harbor. People and (some) animals have been returning to the waters in and around the city. Riverkeeper, founded in 1966 as the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, has played a big role in ushering in that change. The clean water org. made its name suing Exxon Mobil, Ford Motors, General Electric, the Army Corps of Engineers, and other giants that have, at various moments over the decades, harmed the Hudson for profit. Their work was instrumental to the establishment of superfund sites at Newtown Creek and the Gowanus Canal, and they continue to do the day-to-day work of patrolling the river and testing the water quality to track down polluters.

By all accounts, that advocacy is helping. Out on the water, you could see some of the downstream effects of the cleanup. Sailboats from Hudson River Community Sailing, a non-profit that offers maritime and environmental education to local public school students, tacked back and forth along the cliffs at Weehawken all morning. A DEC sludge barge hiked up towards Riverbank Park’s wastewater treatment plant, part of the city’s constant, Sisyphean effort to treat the wastewater before it makes its way into the harbor (NYC alone treats 1.3 billion gallons daily). Underneath the piers nearby, wild oysters clung to the pilings, poking out from below the high tide mark for the first time in nearly a century.

There are caveats, of course, to that optimism: new environmental threats, and serious questions about our current fisheries management practices. Sewage still seeps into the harbor during a downpour, overwhelming the treatment plants. Developments and airport runways continue to encroach on marshland, trickling plastics and new, poorly understood chemicals into the water. The lingering impacts of the last century’s excesses are also substantial: abysmal numbers of shad, river herring, and sturgeon persist here. Still, it is worth celebrating that the Hudson and the waterways connected to it are cleaner than they’ve been anytime in the last century. The days of the oyster carts, and the shad festivals, and the markets full of locally caught fish are behind us for now, but the crowd assembled at the edge of the water offered a glimpse of what a new, healthier relationship with the harbor might look like.

Throughout my career, I’ve attempted to bring people closer to marine life using everything from seine nets, to fish traps, to fishing rods, to classroom aquariums, to nature walks, and goofball adventures that involve wading out into bays and salt-marshes. I’ve taken people on boat tours to show them the city’s seals, and waterbirds, and the terrapins that nest behind abandoned landfills on Jamaica Bay. In the last year, I’ve written something like 25 of these newsletters. The puppets, and songs, and the flotilla felt like a fresh approach to the problem—a new way to bring fish into the lives of New Yorkers without dragging anything up on a line. Maybe at the 50th Fish Migration Celebration, when ‘JAWS’ is turning 100, we’ll finally be able to eat some shad again.

This is incredible?!?

I'm so sad to have missed this and also so excited that New Yorkers want to throw migrating fish a party! That's the kind of connection we need more of--like there's the knowledge and trying to protect, but we also need the love and the joy and celebration, so yay for the latter! (PS. we had similar here with the grunion--like a big nighttime beach party!)