The 120th Anniversary of the General Slocum Disaster

Why Don’t We Remember the Deadliest Accident in New York City’s History?

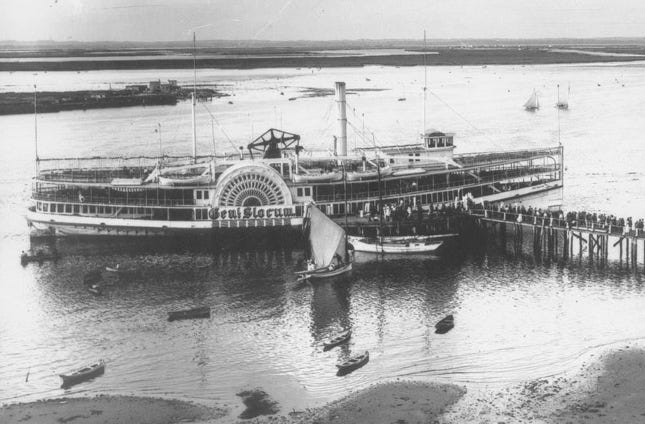

On June 15th, 1904, (120 years ago this past Saturday) the passenger ship General Slocum set out at 9:30 AM from a pier on 3rd Street, on the east side of Manhattan. The boat was a 260-foot triple-decker steamship–a “sidewheeler” propelled by two huge paddle wheels just aft of midship on each side.

Sidewheelers look kind of weird and don’t really resemble any of the boats you’ll see on the water today. For a brief moment, though, before the kinds of propellers that large boats use today became dominant, they were everywhere. Today, most are either retired or growing barnacles and algae on the bottom of the ocean. To me, they have an almost eerie, futuristic look, like something you’d see in the background of a science fiction movie.

The General Slocum was a privately owned excursion boat, a type of bygone ferry that used to take New Yorkers from lower Manhattan and Brooklyn to the Rockaways and other remote (and at the time provincial) shorelines on the outskirts of the city for adventures and day trips. It only ran for about half of the year, when the weather was nice. The area it covered was, in the parlance of the day, the “bay and harbor of New York and Rivers tributary thereto, Long Island Sound, and coastwise between Rockaway Inlet and Long Branch.” Basically, it brought New Yorkers to the Rockaways, up the Hudson, out to Long Island, and up and down the Jersey Shore. It’s a ferry that, if it was around today, I’d probably be riding on a lot.

She was owned by the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company, and sometimes ran scheduled trips where anyone could buy a token. That day, she had been chartered by a Lutheran Evangelical church in lower Manhattan. Over 1,300 people boarded at 3rd street, almost all of them women and children from a small German immigrant enclave called Kleindeutschland (little Germany) on the Lower East Side. The plan was to steam out to Eaton Neck on the North Shore of Long Island, picnic at a scenic spot called Locust Grove, and then head back in the evening. There was a band playing on the second floor promenade deck. The route would take them up the East River, through Hell Gate, and out into the Long Island Sound.

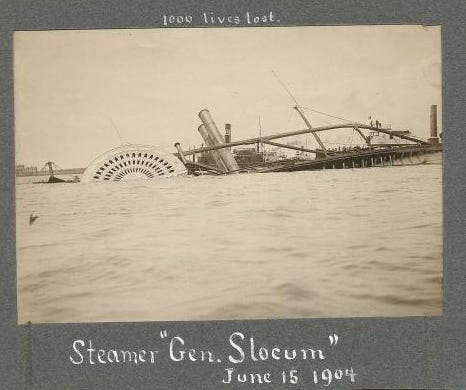

About half an hour into the trip, a fire broke out and spread quickly, engulfing large sections of the ship. Then, for the next twenty minutes, just about everything that could go wrong did. The fire hoses, which had been poorly maintained, fell apart. Efforts to fight the flames were quickly abandoned by the crew, who were new that season and had never done a fire drill. When the captain became aware of the emergency, he accelerated, fanning the fire and inadvertently spreading it before deliberately running the boat aground at full speed on North Brother Island. The passengers were largely left to fend for themselves, and hardly any of them knew how to swim. Many jumped into the water only to find that their life jackets, which were made with rotten cork and contained iron bars, fell apart around them and dragged them down.

It was, by all accounts a horrifying, Boschian scene that was compressed into a very short period of time. People jumped, or held on to the rail as the boat burned and sank. A body was retrieved from inside one of the paddlewheel compartments, apparently churned up out of the water by the enormous wheel. For days, the victims washed up around the city. Between the fire and the drownings, an estimated 1,021 people died in the wreck. The General Slocum disaster continues to be the deadliest accident to ever take place in New York City, and the second-deadliest catastrophe overall, after the attacks on September 11th, 2001.

To put things in perspective numbers-wise, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, which everybody knows about, claimed 146 lives. An estimated 300 people perished in the Great Chicago Fire. Around 1,500 passengers (one and a half Slocums) died during the sinking of the Titanic. While the death toll in New York City from the September 11th attacks was 2,753, the population of the city in 1904, when the Slocum went down, was about 2.2 million, just over a quarter of what it was in 2001. What’s more, the passengers who died on the Slocum were virtually all from the same neighborhood.

So what happened? Why doesn’t everyone in New York City learn about this boat?

I had a vague, murky memory of hearing about the accident, or an accident in the East River. I lead bird walks every year on the East River Esplanade, which runs along the Manhattan shoreline right near the stretch of river where the General Slocum caught fire. This spring, while I was giving a tour, I mentioned the notorious currents above Roosevelt Island, where the East River and Hell Gate meet, and that there had been some big accidents over the years when there were more boats in the harbor. A woman in the group who knew all about the Slocum spoke up, filling in some details. Hours later, I was on the subway reading the Report of the United States Commission of Investigation Upon the Disaster to the Steamer “General Slocum,” which is basically the equivalent of the 9/11 Commission Report for the 1904 accident.

If the wreck isn’t something that comes up very often today, it was all anyone talked about at the time. Local newspapers followed the case obsessively. In October of 1904 the commissioners published their report, a scathing 80-page document excoriating everyone from the captain, to the crew, to the life jacket manufacturers, to the safety inspectors who had signed off on the vessel. They even went after the ship. The Slocum (a native New Yorker herself, constructed in Brooklyn in 1890) was, they wrote: “a shell of highly combustible, frequently painted, extremely dry wood–a mere tinder box of the greatest possible inflammability.” What’s more, they noted, she wasn’t unique. Dozens of similar vessels were churning around the harbor on a daily basis: poorly-inspected wooden ships with faulty safety equipment and unreliable, undertrained seasonal crews.

The commission made a list of “Practical Deductions from the Disaster,” the first of which was that the General Slocum was “probably typical in almost all her conditions of the many excursion boats in New York Harbor and, doubtless, elsewhere.” But the last item on the list was the one that got the most attention: “Neglect of master to beach the vessel or to put her alongside of a wharf immediately after receiving a report of the existence of the fire, and his action in maintaining a high speed and creating thereby a strong draft of air from forward, sweeping the flames aft.”

Accounts of exactly where on the water the fire was discovered are inconsistent, as are the reports of at what point the captain, William Henry Van Schaick, became aware of it. The entire incident took place over the course of about 15 minutes in Hell Gate, a perilous stretch of water that connects the East River to the Long Island Sound. It’s basically the Bermuda Triangle of New York City–a place where countless ships have been wrecked by hidden reefs, shoals, and other barriers to navigation over the centuries. All of those risks are exacerbated by notoriously fast currents. I’ve been through it a few times and even today, after a century of government projects to clear up the worst hazards, it really does feel like you’re on rapids. The current slingshots boats of any size around the narrow curve, which is lined by rocky protrusions on both sides. I can’t imagine doing it on a 260-foot boat, although the pilots that move barges around the city still do.

The commissioners argued, based on some testimony that placed the discovery of the fire earlier and further west than the captain and his pilots claimed, that Van Schaick should have beached the Slocum sooner, near a shoal called Sunken Meadows, or alongside Ward’s Island (now Randall’s Island) or Bronx Bills, where more passengers might have been able to escape to shallow water before the fire got out of control. He was also criticized for the angle at which he ultimately beached the boat at North Brother Island, a head-on hit that left the stern in deep water. He and his pilots ultimately leapt to safety in the shallows from the front, where the pilot house was, while passengers trapped by the fire on the stern were forced to jump to their deaths in much deeper water.

Van Schaick was in the habit of joining his two pilots once the vessel began entering Hell Gate, and all three claimed that the news of the fire, which came to them in the pilot house through a speaking tube (exactly what it sounds like) on the main deck two floors down, reached them only after the boat had already passed the other shallows where they might have reasonably beached the vessel earlier. Once the boat was beached, the captain claimed, he tried to make his way down to the main deck to assist passengers, but the subsequent collapse of the stairs and sections of the middle deck forced him to jump.

The commissioners interviewed hundreds of survivors, and to resolve the numerous inconsistencies in the stories, they gave special credence to testimony from passengers who claimed to have noticed landmarks at various moments during the experience. They gave less weight to accounts that included street numbers, which in my opinion probably excluded some of the recollections of people who were actually familiar with the city’s shoreline.

Today, we have a better understanding of what mass panic can do to people’s memories, especially during chaotic events. It’s impossible to say what really happened, but in general, when we’re talking about who had the best point of view with regard to the boat’s position in the river, the seasoned sailors who were navigating in the pilot house up top are in the running (even if, as the commissioners noted, they had reasons to portray the events in a way that minimized their own responsibility.) The notion that “the captain always goes down with the ship” is one of those sayings like “the customer is always right” or “possession is nine-tenths of the law” that seems obvious to everyone except the people who work in the industry in question. Van Schaick, who had disfiguring burns all over his face and permanently lost the use of one eye, was obviously in the thick of the flames for at least a portion of the accident. Jumping from a burning structure isn’t exactly a “choice.” He spent the years between the wreck of the Slocum and his trial petitioning for fire extinguishers to be made mandatory on ships.

In 1906, Van Schaick was sentenced to a decade of hard labor in Sing Sing, only to be pardoned by President Taft a few years later, leaving the extent of his culpability an open question. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York in an unmarked grave, which was later discovered and publicized by historians. The cemetery website has a note claiming he was “vindicated on all charges,” which I would call a stretch, but it is interesting to think about how much responsibility Van Schaick actually bears. Frank A. Barnaby, the owner of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company and Van Schaick’s employer, was never held liable for what happened.

For a few months, as I’ve been thinking about why the General Slocum is so much more obscure than say, the Titanic, I’ve been asking just about everyone I talk to and meet–especially fellow born-and-raised New Yorkers–if they’ve ever heard of it, and what they know. The two people I spoke with who recalled the story in significant detail were a City Island resident named Russell Schaller, who I met at a bar while reporting on a story up there, and my friend Leo Martinez. Schaller, who is now retired, had a long career working on the water—first in shipbuilding on Long Island and later, when the shipyards closed, in boat salvage and mooring installation on City Island. Leo works on Hudson, running the operations department at a local maritime and environmental non-profit where he and I were coworkers for years. Leo learned about the Slocum from his 11th grade history teacher at Manhattan Business Academy, Mr. Walter, who assigned a book that had a chapter on the accident. Schaller, an old salt with a big white beard, seemed to have just kind of absorbed it through osmosis after a career on the water.

For nearly everyone else for whom the event rang a bell, the disaster was a hazy, distant memory—something that they’d maybe heard about once or twice but didn’t really remember. That’s basically how it’s remembered in New York today. There’s a touching, if small memorial in Tompkins Square Park commemorating the tragedy (a few people left flowers on Saturday, for the anniversary), and a plaque in Astoria Park above a railing that looks out at Hell Gate. Nobody talks about the Slocum much, and the 120th anniversary passed without a lot of fanfare. The oldest survivor, Adolla Wotherspoon, was just a few months old at the time of the accident and died at the age of 100 in 2004. She had no memory of the fire or the crash, and always loved the water, swimming and traveling on boats throughout her entire life. In 1999, at an event commemorating the tragedy, she offered up a simple explanation of its relative obscurity: “The Titanic,” she said, “had a great many famous people on it.”1

I suspect that it also has to do with the community that disappeared. I have tried and failed to imagine what it would have been like if everyone who died in the World Trade Center had been from the same neighborhood. Kleindeutchland, which basically vanished with the Slocum, is half the story of June 15th 1904: an entire neighborhood swallowed by Hell Gate in under half-an-hour. Martinez, who married a native German woman, told me that plenty of Germans he’s talked to know all about the disaster, which is still taught at German schools, even if my teachers in Brooklyn skipped it. That the United States fought in two long, brutal wars against Germany in the decades that followed probably didn’t do much for the legacy. It seems safe to assume that between 1914 and 1946, interest in local German heritage and history was muted.

But I think the biggest reason—or at least the most interesting one, to me—is that the city’s relationship to the water is much less prominent today than it was then. The forest of masts that used to line the edges of the city has been cleared, and the age of the New York excursion boat and the sidewheeler steamship has come and gone. The old piers have crumbled into the water, leaving behind black fragments of pilings that jut up from the surface at low tide. The local fishing economy has virtually disappeared. Rivers and channels, which have shoals, hidden rapids, and rich ecological communities, are blank spots on most people’s mental maps.

But if you poke around, these places are full of stories. People I teach are constantly amazed to learn that there are seahorses and eels and juvenile sea bass hiding out in the mazes of rockweed and ribbed mussels down there. New Yorkers don’t spend much time on our estuary, or most of us don’t, but it’s not our fault. The water is often blocked by highways and chain link fences and piles of uninviting riprap. The currents are dangerous, and when it rains, sewage and trash pours out of overflow pipes. There isn’t a lot of access, and the result, for most of us, is that the waterways are abstractions we pass through in the subway or see from the edges of the city, but rarely get to really use or navigate. North Brother Island, which once held asylums and hospitals, and rehabilitation facilities, but also hosted day trips, and picnics, and clambakes, has been closed off for half a century. As far as we’re concerned today, the General Slocum might as well have crashed into the moon.

I hope you enjoyed the first Landlubber! I have no paid subscription option right now, which means I’m doing this purely for fun (aka attention!) If you know someone who would be interested in reading this sort of thing, please share it with them. You can just forward them this email, or give them this link to the main page, or text it to them. Actually, there’s a button just below that you can push. A few people have said “why didn’t you add my email to this,” but all of them had it in their spam folders, so if someone says “Russell didn’t include me what’s his deal,” just tell them to check their spam folder! They can also just add their email! I didn’t leave anyone out on purpose.

The next letter will be about ecology/wildlife, and I promise not everything I send out will be about New York City.

I tried to get this out by Saturday, which was the actual 120th anniversary of the Slocum disaster, but then I remembered nobody checks their email on Saturday and I gave myself a break. It looks like there was a small commemoration ceremony at All Faiths Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens, where many of the unidentified victims were buried at the time. If you learned about the General Slocum in school, or your parents told you about it, or you have an opinion about it, feel free to reach out and let me know. I’m obviously interested. You can just hit the reply button on the email. Hopefully most of these newsletters won’t be so long.

Upcoming events:

I’m leading a free intro to birding class for the NYC Bird Alliance (formerly NYC Audubon) on the morning of July 13th in Marine Park, details here. NYC Bird Alliance also has lots of other free walks on other days in other places, too. Here’s a link to the calendar.

RISE Rockaway and NYC Plover Project are leading a bird walk on the east end of Rockaway on Saturday July 6th. Details here.

There are Horseshoe Crabs everywhere in bays and estuaries from Massachusetts down to Delaware right now. These are cool and prehistoric life forms, virtually unchanged for 450 million years, and I recommend going out at night during high tide, when they beach themselves to spawn. I go every year and I never get bored of it. All week, the American Littoral Society is doing horseshoe crab walks and tagging events with the public from Gateway National Recreation Area all the way down to Slaughter Beach, Delaware. Dates/Times/Locations here

Estuary News:

There are two black-bellied whistling ducks in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, way outside their normal range, which I tried and failed to see yesterday with my dad. We saw other cool stuff though. There’s also a flamingo hanging out in the Hamptons on a pond where Jay-Z and Beyoncé have a house.

There is also a Man vs. Bird saga playing out in Hoboken, NJ right now. A local birder who goes by Mr. Train is trying to force the city to revoke Weeks Marine’s permit to use a pier, arguing that the company has violated a federal law by trying to evict nesting common terns. I’m rooting for Mr. Train, although I also like the Gateway Tunnel Project.

Great article. Perfect balance of seaweed and barnacle. Hard to believe so many New Yorkers, including myself, have never heard of this before. I imagine this played a large part in sculpting the legacy of fire safety training in USCG licensing, which now plays a central role.

Fascinating topic and great illustrations. Thank you for bringing it to my attention.