Hello, beloved readers! I hope you’re enjoying the final days of summer by swimming, eating ripe tomatoes, and watching little sandpipers run back and forth at the tideline.

I’ve been very busy on a few projects that I’ll tell you about soon, and have been reading diligently about Maine’s environmental history for the second installment of my previous letter about a civil war era bullet in Muscongus Bay (i.e. reading about Maine’s environmental history for you!) That letter isn’t ready yet but I wanted to share information about my upcoming tours, many of which are free! To hold you over, I have a short note about how to enjoy shorebirds.

First, the tours:

On September 17th, October 19th, and November 2nd, I’ll be leading walks for the New York City Bird Alliance (formerly NYC Audubon) in Rockaway, where I know many of you live, work, or have other connections.

Those walks will go through the Rockaway Beach Endangered Shorebird Nesting Area, which is a beautiful stretch of beach in Arverne that’s closed to the public during the summer for nesting least terns and piping plovers. Some of you have been on RISE/NYC Plover Project walks I’ve led out there in the past. It’s remote, stunning habitat, and it has a lot of healthy dune vegetation that most city beaches have lost due to trampling and erosion. There are always plenty of birds there, but I’ll also spend some time on seashells, dune ecology, local history, fish, marine life, etc. We’ll be meeting at the boardwalk and Beach 60th Street, walking east on the beach, and then returning through the sparkling new Arverne East Nature Preserve on the north side of the boardwalk, which we’ll enter at 44th Street. Unlike the beach, the nature preserve has concrete paths throughout so if moving over soft sand is difficult for you, feel free to meet us at the half-way point around Beach 44th street and the boardwalk. You can register for those tours (not required but helpful) on the NYCBA website at the links below.

Those tours are on:

Tues September 17th from 5:30 PM- 7:00 PM

Sat October 19th from 9:30 AM- 11:00 AM

Sat November 2nd from 9:30 AM- 11:00 AM

Other free bird/nature walks I’ll be leading include:

An NYC Bird Alliance walk with Friends of the East River Esplanade on September 18th, meeting at East 96th Street and the East River at 6:00 PM

A walk in Canarsie Park from 9:30-11:00 AM on Sunday, October 13th

An outing in Staten Island’s Snug Harbor, on November 12th from 8:00-9:30 AM

I’ve also got more Classic Harbor Line boat tours coming up in October. These are billed on the CHL website as “Urban Naturalist Tour: Fall Foliage of the Grand Palisades,” and can be booked as early as today! The boat travels north, up the Hudson River to the tip of Manhattan, and then back to Chelsea Piers. As with my previous Classic Harbor Line tours, a ticket comes with a free drink, food, and my affable musings on American shad, the environmental history of Manhattan and New Jersey’s shorelines, and local ecology! I obviously can’t promise any individual bird on any one trip, but raptors love to migrate along the cliffs over there and last year we saw bald eagles on every single one of these. If you can’t make mine, Gabriel Willow is leading on other dates in October and more in November! Just make sure you book the ones called “Urban Naturalist Tour,” or you won’t have a cool nature guide!

The dates for those are:

Friday October 11th at 10:00 AM

Wednesday October 16th at 3:00 PM

Thursday October 17th at 3:00 PM

Friday October 18th at 10:00 AM

Sunday October 20th at 1:45 PM

Sunday November 10th at 1:45 PM

I’m planning to start pinning a tour schedule at the top of this newsletter on the main page. You won’t get an email when I post it, but it will be somewhere you can visit (or send people) if they’re interested in finding tours (they should just subscribe, though.) I’ll let you know when that’s up.

Okay: now shorebirds!

If you’re a birder like me, you know that those birds can be difficult to identify, especially this time of year when the juveniles and molting adults are all mixed up in big flocks. This isn’t going to be a comprehensive guide to them or anything, but I know they’re hard and some days, even I go to the beach and feel totally perplexed by them. On those occasions, I figure out one species, and then work my way out of the woods bird-by-bird. I think of it kind of like tuning an instrument, where you can feel lost until someone plays an E or whatever, and then you have a point of comparison and can rebuild everything else in relation to that.

The fact remains: learning to identify those species is a huge pain in the ass, and if you’re ever feeling kind of dumbfounded or demoralized by peeps (the small ones) or other tricky shorebirds, just remember that you’re not alone. A tidbit on semipalmated and western sandpipers from Kenn Kaufman’s excellent book A Field Guide to Advanced Birding:

“For years, birders separated them mainly on bill length - even though the average difference involved mere millimeters, and even though they were known to overlap. That bubble burst in the 1970s, when it was pointed out that the hundreds of Semis reported on Christmas Bird Counts in North America were probably ALL misidentified: they were probably all Westerns, since practically all real Semis spend the winter farther south.”

These birds are difficult! Nothing terrible happens when you misidentify a bird.1 Relax, have fun, and enjoy the scuttling back and forth and the funny little noises. Birding is supposed to be fun, and while there’s really no wrong way to do it, if you’re not having fun because you’re stressed out, you are kind of doing it wrong!

There are tricks to telling these shorebirds apart, some of which I always remember and others of which I only sometimes remember, but the best way to learn them is to spend a lot of time looking at them! That means keeping your eyes on the birds, and not, say, flipping through a field guide, or taking out your phone to type “shorebird season goes hard fr” into twitter. Eventually, you will get that wonderful feeling that you have with other bird species where you just recognize them right away, as if they are old friends. (Then, you’ll go home, look at the photos you took, and realize that you misidentified a bunch of them, or missed something cool.)

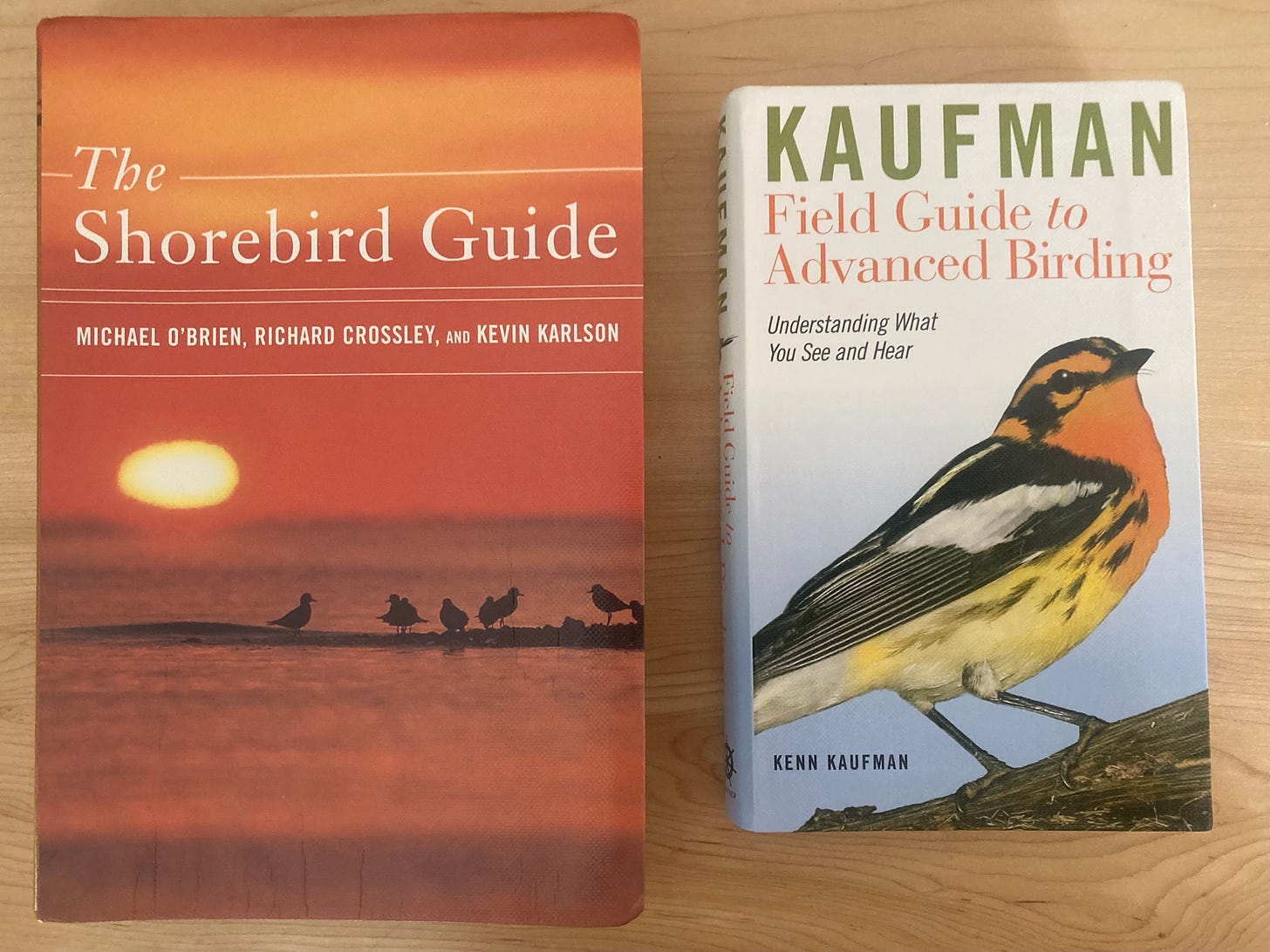

My favorite field guide to these birds is The Shorebird Guide by Michael O’Brien, Richard Crossley, and Kevin Karlson, which has a bunch of photos of mixed flocks that get more and more difficult as the authors introduce new species. It’s a big, gorgeous book with a soft waterproof “duck-back” cover, and it’s probably the only field guide of the many I own that I have read in order page-by-page (as opposed to flipping around at random, or seeking out a specific species). The authors do a very good job at pushing you to think about what to look for when you see these birds (structure, shape, bill size, but also how they’re moving around!)

My biggest tip for looking at shorebirds is: try to see the big picture! Identifying bird species is great, and it’s a fun way to open yourself up to the biological diversity around you. Learning the field marks is also a lot of fun. I love it. We’ll do a lot of that sort of thing if you come on my walks this fall. That said: sometimes, when we’re looking at, say, primary feather projection, or spending a long time watching a single bird to see if its legs are really black or just muddy (I did this last week for about 20 minutes with what I ultimately decided was a muddy least sandpiper), we can miss the most interesting things about these animals!

Lots of the tiny little shorebirds that are around this time of year are bolting down from Arctic tundra. They live astonishing lives, nesting on vast expanses of shoreline grasses and bizarre, remote moonscapes where polar bears and lemmings and snowy owls live out their own survival dramas. Twice a year they fly thousands of miles up and down the continent, and wherever they stop, they have to find a nearly limitless supply of food so that they don’t die of starvation or exhaustion.

In my horseshoe crab spawning letter this spring I mentioned the red knots and other shorebirds that bulk up on horseshoe crab eggs in the spring, but those eggs are all gone now. In the fall, a lot of these birds are eating small crabs, mollusks, and marine worms. The reason so many shorebirds spend so much energy running back and forth at the shoreline, fleeing from waves and risking getting pummeled, is that there is a huge amount of life just centimeters under the wet sand there. Scrape away a thin layer and you will see some of it: gorgeous, rainbow masses of little coquina clams, and teeming aggregations of larval sand crabs.

Variations in the plumages of small shorebirds can be subtle, but shoreline ecology in general is not. Life along the ocean really smacks you in the face in a great way. Go down and grab a little handful of sand where those birds are feeding and you will be holding a small aquarium. (The video below is a mass of coquina clams (Donax variabilis) on a beach in Rockaway in September a few years ago.)

Birding (meaning, here, the hobby of identifying birds you see in the field by species) can sometimes be a limiting hobby in my opinion (please don’t yell at me!) For one thing, it places an emphasis on birds over all of the other amazing wildlife you can see outside. It also pushes us, at times, to think about the wrong things. Occasionally “what species is that” is the most interesting question you can ask about a given bird, but it’s often much more rewarding to ask questions like: “what is that bird doing here?” In addition to opening your eyes to the intricate, wonderful ecosystems those birds are interacting with, questions like that can also help you with the identifications.

One example: semipalmated sandpipers and sanderlings sometimes engage in what a lot of field guides call “sewing machine” type feeding, where their bills seem to probe in and out of the wet sand quickly like needles on a sewing machine. Least sandpipers and western sandpipers (and most plovers) tend to kind of peck at the surface, taking a few steps between bites like someone looking for sea glass (me). The “sewing machine” birds are feeding by touch, probing their bills around to find buried food they can’t see, while the ones that peck at the surface are feeding on things they can see. That’s interesting to me, and helps me identify the birds. It also gives me some footing to start thinking about evolution, the environment, and, (if you really can’t get off the field identification thing) how their bills are shaped!

This is explicitly not a birding newsletter. I like to think of it as a shoreline and ocean environment and culture letter, so: sorry to all of the non-birders for this week’s birding focus! Coming up soon at Landlubber we’ll have more on Maine, some notes on dune ecology, and my very own fish chowder recipe.

Here’s some stuff I’ve enjoyed reading in the last few weeks:

A story from Jesse Pesta about the quixotic mission to save a storied ocean liner named United States, which is currently being evicted from its pier in Philadelphia. If you know someone who has room for a boat the size of the Chrysler Building, please reach out ASAP to Susan Gibbs.

A depressing overview of the environmental practices around the seafood we buy in the United States from Carl Safina and Paul Greenberg. I use the word “role model” ironically a lot, like when I see somebody shaking a vending machine to try to get a free snack and say “that guy is my role model,” but I really did grow up reading the books that these guys wrote and looking up to them.

I’ve also been enjoying Sabrina Imbler’s newsletter Creatures of NYC, which you can subscribe to here.

And here’s a photo of a coquina clam resting on my finger for scale:

An exception to this rule: don’t report a super-rarity that will get people taking off work or driving in from out of state or whatever if you aren’t sure you’ve seen the bird! People make mistakes and that’s fine, but if you tell everyone there’s a unicorn in your neighborhood, people are going to be annoyed if it turns out to be a horse.

I love the busy coquina clams! I'd have said often they are able to burrow back down out of sight quickly, even before the next wave disturbs. Is it rare to see such dense aggregations exposed as in your video? Come to think of it, perhaps the very fact of how dense they were in that case resulted in them not being as able to dig down as they usually do in sand? Where I've seen them, they are much less dense and rarely if ever have I seen them exposed between waves; have to scoop up a handful of sand to see them contorting their foot!